The riff that doesn’t sit in a guitarist’s hands

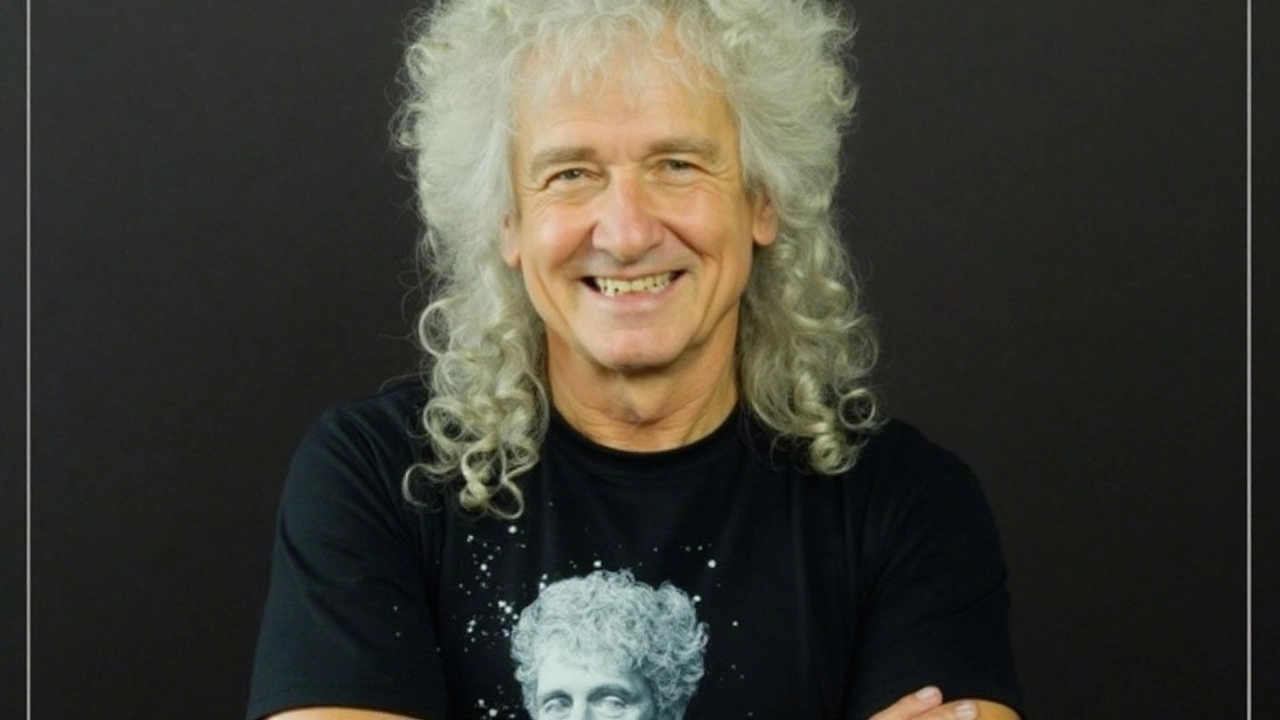

Here’s a twist you don’t expect from a rock icon: Brian May still finds a famous chunk of Bohemian Rhapsody awkward to play live. Not the solo, not the harmonized fanfare—he’s talking about the riff that drops after the operatic section when the band kicks back in. It was born on Freddie Mercury’s piano, and that’s the whole problem. Piano parts often look elegant on paper but can turn into finger twisters on guitar.

May has described it bluntly as “the most unnatural riff to play you could possibly imagine.” Why? Mercury loved octaves. On a piano, jumping octaves is a tiny shift of the hand. On a guitar, octaves can force wide stretches, string skips, weird position changes, and little bursts of movement that don’t line up with the way a guitarist’s brain maps the fretboard. Add a key like B-flat or E-flat—friendly on piano, awkward on guitar—and your go-to shapes disappear.

That’s the technical bit, but there’s some history here too. When Queen broke the charts open with A Night at the Opera in 1975, the rock world was about to be shaken by punk and, not long after, a new wave of flash from players like Eddie Van Halen. Two-hand tapping had been around in various forms since the ’60s, but Van Halen put it dead center on a mainstream stage. May didn’t chase that. He kept the melodic singing tone, the orchestral layers, and the drama. The press loved the arms race—who’s faster, who’s flashier—but Queen doubled down on songs. That makes this admission even more relatable: even the master of melody runs into a part that’s just not built for guitar.

Bohemian Rhapsody is a perfect example of why. It’s stitched together from distinct sections that change feel, harmony, and texture. In the studio, they had unlimited takes, layered harmonies, and time to make every corner click. Onstage, you get one shot. And unlike the vocal “mama” tapes that roll during the operatic break, the band has to lock in by feel the instant the heavy section slams back. That’s where the riff lives—big, brash, and stubborn under the fingers.

Guitarists know the traps: fast octave jumps, string-skipping at tempo, and rhythm accents that land in places your picking hand doesn’t love. May uses a sixpence as a pick, which gives him that singing attack, but it also means he must be precise or the strings will fight back. The Red Special—the guitar he built with his father—has a unique feel and response, and that’s part of the charm. It also means there’s nowhere to hide if your timing is even a hair off.

Translating piano to guitar is a specific headache. Piano supports huge intervals under one hand and can voice wide chords without the physical hops a guitarist needs. On guitar, those leaps can force a choice: shift your hand fast, skip strings cleanly, or re-finger the part in a way that keeps the character without copying every move. Now do that while the lights blind you, the crowd screams, and the band hits the section at full blast.

- Octave leaps feel natural on piano; they demand wide stretches and string-skips on guitar.

- Keys like B-flat or E-flat remove helpful open strings, forcing less comfortable shapes.

- Rhythmic accents baked into the piano part don’t always match standard picking patterns.

- Live cues after a taped section leave no wiggle room for settling in—hit it, or it’s gone.

May has said he can play the riff at home without drama. In the quiet of a room, you can relax your grip, breathe, and find the pocket. Onstage, especially when Bohemian Rhapsody closes the night, adrenaline pushes the tempo and tightens your hands. That’s when tiny movement patterns—those awkward string jumps and shifts—get harder. And when the song is this famous, you feel every millimeter of it.

There’s also the psychology of the finale. Queen shows often build toward Bohemian Rhapsody, with the opera section running from tape and the band re-entering like a rocket. The audience knows every accent, every drum fill. May steps to the front for the heavy riff and the melodic lead lines that follow. It’s a celebration and a pressure cooker. One fluffed octave, and you hear it. That’s the flip side of writing parts that don’t sound like anybody else: they also don’t play like anybody else.

What’s striking is how consistent May has been about this over the decades. Even as guitar culture shifted toward technique—tapping, sweep picking, blazing alternate runs—his focus stayed on storytelling. His tone through Vox AC30s, those vocal-like bends, the layered harmonies he tracks in the studio—these are the things people hum. Still, he’s honest about the fact that not every part sits neatly in the hands. The Bohemian Rhapsody riff just happens to be one of those stubborn ones.

Listen closely at a show and you’ll hear why it matters. The riff sets the table for the solo and the final vocal drama. It has to punch, it has to sit tight with the drums, and it has to make the key feel like home even if the fretboard is fighting you. When it lands, it’s euphoric. When it pushes a hair, you feel the band digging in to pull it back. That edge is part of the live magic—and part of what May is getting at when he talks about the challenge.

There’s a small lesson for players here. We tend to think of difficult guitar parts as fast runs or wild techniques. Sometimes the hardest thing is a line that looks simple on paper but forces your hands out of their comfort zone. That’s the nature of translating between instruments. Mercury thought like a pianist. May thought like an arranger. Somewhere in that handoff lies a riff that can still bite, even when you’ve played it more times than you can count.

So yes, the guitarist who inspired players from Steve Vai to Justin Hawkins still wrestles with a single, stubborn figure. It doesn’t chip away at the myth; it adds a human detail to it. On the biggest nights, when the lights flare and the crowd belts the last chorus, you can see why he’d call it unnatural—and why he keeps taking it on anyway.